Cheri Ezell-Vandersluis, a former dairy goat farmer, co-founded Maple Farm Sanctuary with her husband Jim Vandersluis. They are both subjects of the documentary film Peaceable Kingdom: The Journey Home.

Let me begin by stating I've always loved animals, but I grew up in a society that treats them as possessions, as things--a "meat and potatoes" world. I had no idea the flesh I consumed came from wide-eyed cows and innocent fluffy chickens. And while I knew I always wanted to work with animals, it took time and several life lessons before I found a job that truly benefited them.

My first growth spurt came when I was employed at a drug manufacturer, as both a histology technician and--brace yourself--autopsy room technician. I was told the research benefited mankind and that the killing of test animals was called "sacrificing." In the logbooks where we recorded autopsy room data, we didn't kill anyone, we "sacrificed numbers." I remember early in my employment, walking to where the dogs--sweet little beagles--were caged and routinely dosed with compounds such as growth promotants, antibiotics, dopamine and a multitude of others. I would talk with them, reach through the cages to pet them, all the while looking into their trusting, unknowing eyes. I did this for only a few days before I was caught and reprimanded for this behavior. I was told test animals were to have no human contact other than dosing, examining, cleaning and feeding since any expression of affection would cause the animal to have a will to live and adversely affect their reaction to the compounds they were given. Well, I tried living with that justification for about four years before I left. My life of discovery had begun.

My next job was at an aquarium. And while I found myself amongst many who adored and cared for animals, we were working for folks who lined their pockets with their blood. I subsequently left the aquarium and spent a short time as a graphic designer before deciding to become a goat milk farmer. I actually met my husband Jim, a dairy farmer, when collecting goats for my business. We became inseparable.

One day I entered the barn while he was milking and noticed an obviously ill calf. When I questioned what would happen to her, he told me regardless of the calf's illness, she would be sent to a livestock dealer where she would be sold for meat. I learned that dairy cows have to be bred every year in order to continue to produce milk, and how their calves are taken from them shortly after birth--they're lucky if they get colostrum from their mom, which is the first milk that is important for their survival. While some of the calves are kept as replacement heifers, most of them are sent to slaughter or the veal operations, which is a very short life, and not a happy life.

The verbalizations made by mother and baby as they bond are just one small aspect of their emotional lives that we humans tear apart. The mother calls for her baby for many days after they're separated. How can such a thing ever be called "humane?" The farmed animals who aren't killed shortly after birth go through experiences like tattooing, branding, ear tagging, tail cropping, castrating... all without benefit of anesthesia. A common practice in docking and castration is the use of an "elastator" that places a tiny rubber band around whatever appendage is being removed. The pain from this technique lasts for weeks as the body part has the blood supply cut off and ultimately falls off. Some other techniques include crushing and cutting without sedation and/or anesthesia. Is this humane treatment?

In time, our consciences would not allow us to continue milking our cows for the purpose of producing dairy products. Instead, we increased the goat herd and began to sell goat milk. I thought, perhaps this was an alternative--I could have the animals and I could have the milk, and the babies could go for pets. We loved the goats, babies and adults, and we wanted them to have the best life that they could while they were with us. So yes, they were fastidiously taken care of and allowed to have as much freedom as we could give them.

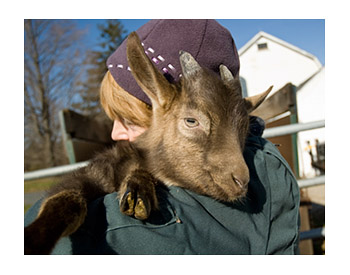

Over time, Jim started getting so much closer to the animals, whereas before when he was working with dairy cows, he was always so busy he could not have that closeness. In those days, when a calf was born he would call the livestock dealer, go milk some cows, and he wouldn't even see the calf go. But now he was holding the baby goats. He was taking care of them, looking into  their eyes, and I was too. And they would look back with this obvious trust and love. their eyes, and I was too. And they would look back with this obvious trust and love.

But we still had to make a living, and I soon realized I couldn't possibly make enough money from the amount of milk that I was producing and then have the babies go for pets. There were just so many babies, every year you have to have babies. And not very many people are interested in buying goats as pets.

In certain communities, it's tradition to have baby goat meat during the Easter holiday. So our farm was overwhelmed every Spring by people looking for baby goats. We would weigh the 25-35 pound kids, and the customers paid. They were then hogtied and literally thrown into a trunk or the back of a pick-up truck like a piece of luggage. Jim soon was saying, "I will carry the goat," and he would gently put the goat into their vehicle. One day we were standing by the gate of the goat barn, listening to one of our baby goats being driven away, crying in the trunk of the car. It was at this horrific moment that Jim and I looked at each other with tears in our eyes and began our journey to a no-kill life.

It was a frightening time for us because the goat milk and the kids were part of our income in supporting the farm. But we later witnessed the deaths of some of our baby goats, and that finished the process of altering our life course. We watched in horror when a goat was roughly held in preparation for his throat to be cut. He cried out with such terror, and then the knife quickly crossed his neck. It was not an instant death. The struggle went on for twenty or thirty seconds, but it seemed like an eternity.

So yes, you can raise them and have them graze in green fields of grass and brush them every day, but when you ultimately put them in someone's truck or on a livestock trailer, and they go to be slaughtered, I don't care if you say a prayer before they're slaughtered or if you simply send them into the slaughterhouse. Their throats are still slit. They feel pain. They gasp for air. I can't imagine what goes through their minds. If you look into their eyes you can see the fear, and the abandonment. You've loved this animal, and then you've sent them off to this horrible death. So I can't imagine "humane" and farming going together for raising any sentient being. The words just don't go together for me.

Jim and I have since left the dairy industry and converted our farm into a sanctuary for farmed animals, wildlife, and companion animals. Now when I go to the grocery store, I have such a hard time going by the meat department. It sounds strange because I used to shop in the meat department like everyone else. And now I have a hard time even looking. I see people going over and selecting their cuts of meat, and I want to take them by the hand and explain to them that this came from a living being who had feelings just like all of us. That meat came from a cow who had babies, had a family--or tried to have a family. I want people to understand these are sentient beings who, if left to their own devices, have a real bond with their own kind, and with us humans too, if allowed to. And yet I see people picking up the slabs of meat, and they have no concept of where that meat came from or how that animal suffered when he or she was slaughtered. It's not their fault. It's just the way of life society teaches us, the way of life I was taught before my own experiences led me down another path.

So for Jim and me, there is now a very clear distinction between humane and inhumane farming. Humane farming is cultivating a plant-based diet. Inhumane farming is breeding any sentient being for production and consumption. Now we feel happier and more content, and at peace with what we do. And we try to share our story with people, so perhaps they, too, can make a transition toward helping create a more gentle society.

Cheri Ezell Watch Cheri and Jim share their inspiring story of transformation

in the award-winning film, Peaceable Kingdom: The Journey Home

|